Sub-Aquatic Boats Make Good

Dr. Scott Birdseye is an educator, Doctor of Philosphy and nutcracker collector. He even has a nutcracker from Rhode Island. It’s very neat.

Submarines have shown themselves to be one of the most effective weapon platforms ever devised and their crews to be the best in the navies of the world. This effectiveness was fully illustrated in the Second World War, when American submarines operating in the Pacific theatre were able surmount incredible difficulties to achieve a total victory in their war of attrition against the Japanese Navy and Merchant Fleet. The valor, courage and skill of the men of the American Navy’s submarine force proved the capability of their ships, and finally reversed the long negative history of the submarine.

In the aftermath of WWI, international conferences worked to ban the use of submarines in war. In the United States, President Harding, seeking his “Return to Normalcy”, shelved any attempt by the Navy to increase the size of the submarine force. The 1922 Washington Naval Conference backed this policy by limiting the size of the U.S. Navy, especially in the Pacific.

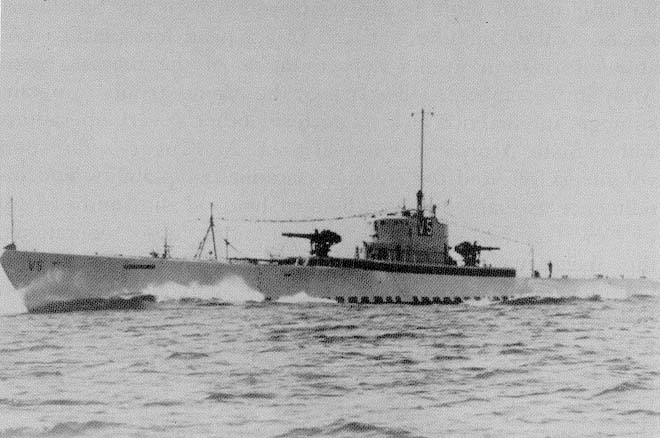

Despite these limitations, the U.S. Navy, in the 1920s, did build a new series of submarines, the V-Class, the design of which was based on German U-boats. These ships, with their large size and armament, would form the basis of the U.S. submarine fleet until the pre-war build up of the late 1930s.

In 1936, after the expiration of the terms of the Washington Naval Conference, the United States began its submarine building program anew. The P, S, and T Class ships were built during this period, and ranked among the best submarines in the world. However, strategic commanders did not consider submarines to be an important part of the navy.

Thus, as Japanese expansion increased in the Pacific and war threatened to break out in Europe, the United States submarine force was woefully inadequate. The United States Navy’s submersible strength in the Far East was based in two groups: The Pacific Fleet, stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the Asiatic Fleet, stationed at the Philippines. The Pacific Fleet Sub-Force, or SubPac, consisted of twenty-eight modern S-Class submarines, while the Asiatic Fleet Sub-Force had only six modern subs out of their total eighteen. Their remaining ships were from the First World War, and were obsolete. Fortunately for the U.S. Navy, the inferior ships of the Asiatic Fleet were destroyed or rendered unusable in the Japanese conquest of the Philippine Islands. When the U.S. entered the war in December of 1941, there were 112 subs total in the U.S. force and seventy-three under construction.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which brought the United States into the Second World War, left much of the Pacific surface fleet destroyed. The Pearl Harbor disaster, coupled with the loss of the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines, left the Pacific Fleet’s submarines to bear the brunt of the fighting in the earliest part of the war. Admiral Chester Nimitz would later describe the situation the U.S. faced immediately following the outbreak of the war: “When I assumed command of the Pacific Fleet on 31 December 1941 our submarines were already operating against the enemy, the only units of the fleet that could come to grips with the Japanese for many months to come.”

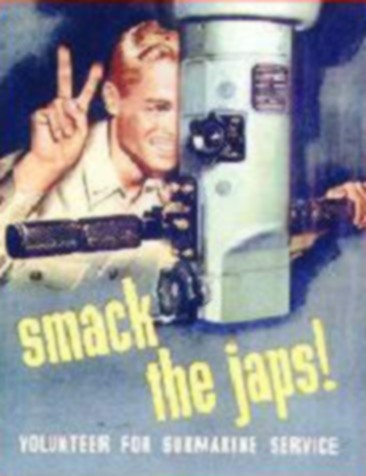

The Chief of Naval Operations issued an order to “Execute unrestricted submarine and air warfare against Japan.” The main goal of the submarine force was to be a war of attrition against Japanese merchant shipping. This battle would force Japan into surrender by cutting off resources from their newly captured empire in the Pacific. The initial strategy would be to engage in constant attack on vital supply lines to achieve a commercial isolation of the Japanese home islands.

In 1941 Japan had six million tons of merchant shipping. By far, the Japanese had the largest industrial economy in the Far East, although it was still far behind the United States and the European powers in output. Although many Japanese leaders, such as Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, saw industry as unimportant compared to the spiritual strength of the Japanese people, modernization prevailed in Japan. Production output had increased in Japan from 10.2 billion yen in 1930 to 15.8 billion yen in 1936, and Japanese industry had grown most particularly in metallurgy, machinery, and chemical production, industries which provided the materials necessary for waging modern war.

Oil was the most vital and necessary resource for the continued operation of Japan’s growing industrial complex. Ninety percent of the world’s oil was in the hands of the Allied nations, and the Axis powers controlled only three percent. The pre-war U.S. oil embargo against Japan further limited its industrial output by cutting off nearly ninety percent of Japan’s oil. These factors increased the importance of Manchurian and Indonesian oil to Japan and of the merchant shipping which was necessary to transport the oil to the factories and industries where it was needed. However, despite the importance of such shipping, the admirals of the Japanese Navy believed that the war with the United States would be fought by warships and decided by one decisive battle. The Japanese admirals did not view a protracted war of attrition as heroic, and thus it was felt that the United States Navy would not engage in cowardly attacks on merchant shipping. Therefore, defense of vital shipping lanes, particularly those which transported oil, was not a priority.

The Japanese Navy required 1.6 million barrels of oil a month in order to operate at wartime readiness. Without oil, Japan neither could have a functional war machine to defend its newly captured empire nor provide the industrial output necessary to supply and maintain their battle groups. Imperial Munitions Minister Soemu Toyoda spoke of the necessity of these factors: “the shipping shortage and the scarcity of oil were the two main factors that assumed utmost importance in Japan’s war efforts.”

As Japan’s lack of natural resources and dependence on shipping was well known, the Pacific Fleet Submarine Force, the United States’ only available weapon in the East, began their campaign to starve Japan of the resources it needed to continue the war. As this campaign began it met with initial failure, due for the most part to the cautiousness and inexperience of the individual submarine commanders and to technical problems with the submarines armaments. Though U.S. submarines were on constant patrol for the first part year of the war, their attacks were not effective against either the Japanese Navy or their merchant marine. In 1942 the Japanese Navy commented that the weather was a greater enemy than the American Navy.

Despite the timidness and conservative tactics of skippers, the main problem faced by the U.S. submarines was their torpedoes. Due to major design flaws. The Mark XIV, the navy’s primary submersible weapon, had major defects. The torpedoes ran too deep, making it impossible for their magnetically triggered detonators to explode. The firing pins did not work if the torpedoes hit their targets head on; they were too fragile to engage unless they hit their target on a precisely acute angle.

The basic problems of the torpedoes were undetected due to the lack of proper testing, due to the passivity of the Navy Bureau of Ordinance toward submarine activities. The Torpedo Station at Goat Island, Rhode Island designed and built the first Mark XIV torpedoes in the 1930s, under the direction of the Bureau of Ordinance, but without any input from the Fleet or any concern about their tactical and operational needs. Testing of the new weapons was not given a high priority due to the eight to ten thousand dollar cost of a single torpedo. The Bureau believed that live tests were not cost effective. Thus, in testing the Mark XIV torpedoes were only dummies and any shot that went under the target ship was counted as a successful hit. Therefore the magnetic-influence exploder was never actually tested. Failure of the depth control systems was also not discovered, as the tests were conducted in water which was too shallow to allow for adequate determination of the depth control mechanism’s functioning. Thus, when U.S. submarines were deployed into combat in the Pacific, neither the admirals, nor the skippers had any idea that their main weapon system would not work.

Despite these setbacks, the Pacific submarine force sought, throughout 1942, to blockade all of the Japanese Empire, which extended from Kamchatka in the north, to the Solomons in the southwest, to Burma in the East. Though there was a shortage of submarines initially, there were a large number of vulnerable Japanese transports and merchant ships to hunt. With the majority of the Japanese Navy thoroughly engaged in battle with the American surface fleet, U.S. submarines had little trouble with anti-submarine warfare. Throughout late 1942 and into early 1943, the U.S. submarines’ war of attrition continued to gather momentum. Throughout 1943 and 1944 the attacks against shipping increased by extraordinary amounts until the entire Pacific became a hunting ground for American wolf packs.

The dramatic change in the effectiveness of the submarine attacks, which took place in 1943, was due to several distinct reasons, including the influx of new submarines to increase and widen the attacks, the positioning of new, more bold commanders and skippers, the creation of new tactics and doctrines, the discovery of a solution to the problems which plagued the Mark XIV torpedo, and the increased confidence and experience of the submarine crews.

By the spring of 1943, the SubPac had doubled in size. Thirty-six new submarines had arrived in 1942, fifty-two in 1943, seventy-six in 1944, and by the war’s end in August of 1945 the U.S. submarine force in the Pacific consisted of 169 ships in all, with the majority of them the newest and best in the world. With constant reinforcement, the U.S. was able to extend its submarine activities throughout the entire Pacific.

In 1943 this force was placed under the command of skilled veteran sub commander Admiral Charles Lockwood. Lockwood had distinguished himself as Commander of Submarines South-West Pacific, and was known for his daring aggressiveness and for his willingness to place high demands on his subordinates. As commander of SubPac he was able to replace inhibited and timid skippers with ones that better matched his own style of boldness and cunning. He encouraged adaptation and independence in his skippers and rewarded those who took initiative and formulated their own tactics according to specific situations.

On 24 June 1943, the SubPac, under Lockwood, issued the SubPac Operational Plan, which called for increased offensive patrols, assigned target priorities to different Japanese ships, and gave individual submarine skippers more freedom in their commands. The plan also officially named the disruption of enemy supply lines as the number one priority of the U.S. submarine forces in the Pacific. Increased security and secrecy developed from the plan’s initiatives, as a means of ensuring that the Japanese Navy continued to believe that its weak anti-submarine defenses were working well.

With increased freedom, submarine skippers were able to adapt their tactics and to deviate from standard doctrine when called upon. Attacks began to shift in mid-1943 from surface raids to more effective submerged sorties. Use of radar, which, by Naval doctrine, had been prohibited during encounters with enemy vessels, allowed safer offensives and escapes. New tactics also included the “Down the Throat” attack and “Wolf Packing” both of which produced higher kill rates for submarines.

Operational independence also led to a solution to the problems involved in using the Mark XIV torpedo. Submarine crews directly violated safety and security regulations to reset the depth control mechanisms, which had been giving readings eleven feet deeper than actual depth. Although submarines sunk a large number of enemy ships, less than fifteen percent of those sinkings occurred with the defective torpedo mechanisms. The Bureau of Naval Ordinance finally gave in to the wishes of the fleet, and changed the mechanisms of the Mark XIV in September of 1943.

Despite these advances, it was ultimately the courage and experience of the submariners themselves, which provided the exceptional results of the U.S. war of attrition against Japan. Though inexperienced and uncoordinated at first, constant practice and combat made kills for veteran ships a simple affair. Good crews ran like clockwork, with each man sure of his place and duty, and trusting his skipper for the final word.

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations said of the battle in the Pacific: “Submarine attacks produced immediate and damaging results. . .made it more difficult for the enemy to consolidate his forward positions, to reinforce his threatened areas, and to pile up in Japan an adequate reserve of fuel oil, rubber, and other loot from his newly conquered territory.” Kichisaburo Namura Imperial Japanese diplomat analyzed the war of attrition: “Submarines initially did great damage to our shipping, and later, combined with air attack, made our shipping very scarce. . .Our supply lines were cut and we could not support these supply lines. . .”

In the autumn of 1943 the Japanese came to the conclusion that their shipping was less than one third of what execution of their war plans required. The Imperial Ministry of Munitions stated that if shipping from the Southern Pacific were cut off then Japan would be forced to halt its war efforts. Submarine attacks on oil shipping forced the Japanese to use the majority of their transports for oil, the most vital commodity, leaving little shipping available for other resources, including food. Despite these changes, oil imports continued to decline. Loss of transports and safe shipping routes caused other declines which further reduced the ability of the Japanese industrial complex to support the war effort. Bauxite imports fell 88 percent between summer and fall of 1944. During this same time iron imports fell 89 percent, iron ore fell 95 percent, cement fell 96 percent, lumber by 98 percent, and sugar and rubber imports were totally cut off.

In order to offset losses in shipping strength, the waning Japanese industry was forced to transfer materials from warship production into merchant ship production. This was illustrated by the fact that in 1941 merchant ship construction accounted for 7 percent of steel used in Japan. In 1945 however, it had risen to 46 percent, providing less steel for use in warship construction, maintenance and repair. By the winter of 1944 and early 1945 the oil shortage had become so acute that no petrol was available for motorized vehicles, planes, or for factory power plants. War material production was brought to a near standstill and replacement weapons were unavailable for deployment. In early 1945 transports became so scarce that even sail-powered fishing vessels were conscripted for use in shipping.

In all, American submarines in the Pacific sank 1, 750 Japanese merchant ships of a total of 4.9 million tons, 56 percent of those lost. The blockade of Japan and the destruction of its merchant shipping made reinforcement of their armed forces and maintenance of their war effort impossible, destroying Japan’s defenses and making the home islands susceptible to all manner of attack. The continual attacks on supply lines made reversal of attrition impossible, the weakness of their defenses opened their supply lines to attack, which destroyed their war industry further weakening defenses and allowing more supply lines to come under attack.

The U.S. submarines had played an enormous role in the destruction of Japan, however the enormity of their role was far greater than first appeared. Though they sank large numbers of merchant ships, and 214 Japanese warships, nearly one-third of total Japanese Naval losses, the U.S. subs accounted for only 1.6 percent of the United States Navy, and suffered only a 22 percent loss rate, losing only 44 ships to enemy action out of 288 ships total. The kill to loss ratio of the U.S. submarine force in the Pacific was the highest in the Navy. This success was not achieved overnight however, as the war of attrition struggled through the early part of the war, only to gain momentum in mid-1943.

In all, the United States spent a total of 873 million dollars building the SubPac, a force, which through the skill, initiative, aggressiveness, and courage of its sailors and skippers, was able to send to a watery grave nearly 129 billion dollars worth of Japanese ships, nearly forty-two times the amount spent. More importantly, however, the United States submarine force in the Pacific was able to prove conclusively that submarines, despite their initial difficulties, were an effective weapon. In their war of attrition against Japanese shipping, a war which crippled Japanese industry and war efforts, these “sons of bitches” in their “pig boats” achieved a victory unequalled by any other force in the Second World War.

I am preparing a manuscript in which I plan to utilize submarine warfare tactics (particularly wolf pack tactics and strategies) as the foundation and platform in investigating organizational culture. I would appreciate any information and guidance you could provide. I’ll require the basic rudiments as I provide a background comparison.

Thanks, Joe Woodall

Visiting Assistant Professor

UNC Charlotte

704.687.3041

jwoodall18@uncc.edu