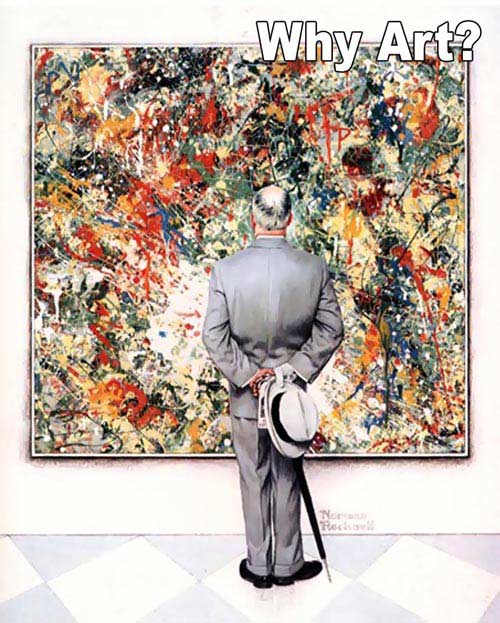

In our country, there is a pervasive notion that art is not only a significant aspect of our culture, but that the fine arts exalt us, lift us up and inspire us. Our tax dollars support some art, based on the notion that the existence of artwork enriches all of society. In the same vein, many schools and universities have required art history and art appreciation courses. This leads to one question; if art really is part of our collective culture, why do we need professionals to explain it to us, why is art not more popular?

Another option is that art is not really a part of our culture at all, rather that it is kept on life-support by a small, but influential, group of artists, collectors and educators and the reason art remains only a small niche field of interest is largely economic. It’s not that people don’t “get” art, rather the economic circumstances make art inaccessible. Most people have developed no interest in art and the truth is that they have no reason to; it’s simply not a part of their daily lives.

The same cadre of influential people, some with the good of society in mind, some with an eye on lining their own pockets, have sequestered art in places people aren’t likely to go while at the same time ensconcing faddish works of abstraction in the few places people go more often.

The Romans, for instance, placed art, lots of it, in the daily loci of every citizen’s life: the bath house and the Forum. The work of the great European painters was, for centuries, to be found available to the public in the one location where they could save their souls: a church.

Unlike the grocery store or work, few people have as a daily stop on their schedule the Museum of Modern Art. Meanwhile, what public art one might see near government buildings visited every couple of months is the abstract, red metal works of Alexander Calder. This is not to limit what meaning there is to be found in his works, but they hardly provide the connection of a Rodin or a Rousseau.

Both Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein were successful Post-War American artists but neither one is directly part of our collective culture. Most Americans have not heard of them, would not be able to recognize their work, don’t see their work on a daily basis and

certainly don’t have one of their paintings hanging in the living room.

Of course, those are some fairly large assumptions. While it is impossible to have a nation-wide referendum on Roy Lichtenstein, we can say that, using a Google-brand search-engine, the painter actually gets fewer results than a common misspelling of the band Nickelback, but ten times more results than Spiderman spelled with two Ns.

Spiderman and Nickelback are a different matter than art. Movies and albums can be mass-produced and mass-production lowers costs and prices. In contrast, art is not mass produced; the closest it comes are with the print editions, the largest of which may only include five hundred to a thousand examples. Even with such numbers, the prices still do not but flirt with affordability.

A DVD will cost you twenty dollars and an album no more than twenty, but even a mass-produced signed print will run you at least five hundred. That is, if you’re looking for such a print in the first place. Most Americans can’t afford to have a piece of art in their homes. Prints may start out at about five hundred dollars, but original works by little-known, but successful artists start at around fifty thousand. As the U.S. Census Bureau reports that median household income in the U.S. is forty-three thousand, most Americans would be forced to choose between a house or a Frank Stella original. Since you need a wall on which to hang a Frank Stella, consumers would tend to pick the house over the painting.

That leads us to the issue of reproductions. For the price of an album, you could have a poster of Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss” on your wall. It seems a good deal since Ronald Lauder paid a hundred and thirty five million for the original. But, a poster is not a painting. Then again, a DVD of Star Wars is not the original celluloid print of the film.

Unlike a painting, a film is not just visual; it involves sound, music, literature and performance, so while the size of the image or its resolution may be reduced, watching a film on DVD still allows a great appreciation of the other elements; the story, the literature, the characters and the sound are still the same, even though the picture may be smaller. An artwork is purely visual and when the visual element is thus diminished the entire work and the experience of viewing are also diminished.

It is entirely different for a book or an album. Original releases may be prized for their rarity, but the work loses nothing in its reproduction. One can experience the same emotions when reading any copy of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” When purchasing a book or an

album, one is buying the work itself, and not a reproduction. Anyone with twelve spare dollars can own “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” not a diminished reproduction, but the music itself. Anyone with six dollars can own “The DaVinci Code,” a non-abridged, non-expurgated, non-diminished version. The only way that one can own a non-diminished version of Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” is to have thirty or forty million dollars to spend.

Members of the general public, those who do not have several million, or even a hundred thousand spare dollars, can still view art in its original form by going to a museum. For many though, they may only go to a major museum once or twice in their lives; major museums tend to only be found in large cities, and this leads to the idea that again, only for a minority is art accessible.

Even on a visit to a museum it is impossible to see everything available. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art has over two million works, it would take a person fifteen non-stop months to give each piece a twenty second view. On a visit, a few pieces may be recognized from books, or ads or school texts, but for the non art expert a few glances at each work in the shuffle from room to room will make little difference in their lives.

People do not seem opposed to art, generally. Many homes have paintings hanging in them, even if they are only cheaply-produced hotel style paintings. But art does not make a direct impact on our culture because we have no way to share it with others and culture, by definition, has to be shared. Anyone can listen to “Pet Sounds,” read Jurassic Park, or watch “Casablanca,” but only the highly rich can afford to view a real Picasso every day.

Thus, all the people in the set of anyone, including the rich, can share in discussion or conversation about a book, a movie or a song, but not everyone can talk with their co-workers about their favorite Niki de Saint Phalle sculpture. Art is expensive and because of this it is not popular and due to this lack of popularity it makes little impact on our real culture.

While some artists, such as Christo and Jeanne-Claude have attempted to make their work widely accessible, many artists seem content to profit off of a hungry, wealthy niche market without making a large cultural impact. Perhaps that is why Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” could rouse a nation to war yet Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” utterly failed in preventing horrors far greater than the Spanish Civil War.

That is not to say that it was somehow Picasso’s responsibility to prevent the Second World War. But when one witnesses the powerful and wide-reaching impact of books, films or songs, it’s disconcerting to see that another such medium, art, can not only fail to deliver that impact, but that its creators and patrons seem so content to continue their existence in a sheltered cocoon while they adamantly claim to deliver a cultural impact which has yet to be felt.